In October 2021, a court in Rajasthan sentenced a man to 20 years imprisonment for raping a 9 year old girl. This case made it to the news because of the exceptional speed of challan to conviction. The police filed the challan (chargesheet) within 18 hours of registering the case and the court convicted the accused within 9 days of commission of the crime. This example is an outlier in our otherwise clogged judicial system where cases, even those which are fast tracked like cases of child sex abuse, can take years to reach any kind of closure. The already burdened justice system is stretched further due to external shocks like a pandemic. The latest crime statistics released by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) in September 2021 provide a quantitative certainty to what had been feared all along — in the Covid affected year of 2020 justice delivery was decelerated further.

Though time alone may not be a sufficient factor to determine weaknesses in our criminal justice system, and its impact may be muted or compounded due to other factors, it is a necessary factor which needs to be studied. In this article, I explore how time interplays with and affects justice delivery, how it impacts the efficacy of proceedings, the quality of justice, and how it can advance or constrict our rights.

Time and Justice

Time has a complicated relationship with the criminal justice system. The phrase ‘tareekh pe tareekh’ (one adjournment after another) immortalises in popular imagination, like nothing else could, the trials and tribulations of hapless litigants on their journey to secure justice. Indeed, when we express concern on the pendency of cases in courts, we are measuring the efficacy of our justice delivery system in terms of time it takes to dispose of a case. Time is also an instrument to advance or thwart justice, as the common phrase, ‘justice delayed is justice denied’ exemplifies. Ascribing time limits to processes is also crucial to prevent state encroachment on rights. For instance, the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC) provides that an arrested person must be presented before a magistrate within 24 hours to prevent any police abuse while in custody.

With respect to challenges posed by high case pendency, in 2000 the Central Government responded with a scheme of Fast Track Courts (FTCs), first recommended by the Finance Commission to dispose of long pending cases before sessions courts. The scheme was discontinued in 2011, but according to government estimates, between 2000 and 2011, out of 38.9 lakh cases transferred to such courts, courts managed to dispose of 32.34 lakh cases. After 2011, following the Supreme Court’s order in Brij Mohan Lal vs. Union of India, the responsibility was passed to states to set up and manage FTCs, which many states discontinued.

Fast Processes but Slow Justice in POCSO

In 2014, the scheme was re-initiated, with specific focus on FTCs in cases of heinous crimes involving senior citizens, women and children. In 2018, 1023 FTCs were specifically set up to deal with rape and POCSO cases (exclusive 389 FTCs for POCSO). This scheme was supposed to run till 2021, but was recently extended till 2023. But a status report by the Central Government as on 31 May 2021 shows that in two years, these FTCs (including POCSO courts) managed to dispose of only 49,511 cases while 1,59,296 were still pending.

Even before FTCs were set up for child sex abuse cases, the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012 (POCSO) combined with the CrPC provided for time bound processes to dispose cases and Section 28 of POCSO provided for Special Courts for ‘speedy trial’. The relevant timelines are:

- Evidence of the child must be recorded within 30 days of Special Court taking cognizance of the offence – Section 35(1) of POCSO

- As far as possible, the trial has to be completed within one year of Special Court taking cognizance of offence – Section 35(2) of POCSO

- In case of rape of a girl child, trial has to be completed within two months from commencement of examination of witnesses – Section 309(1) of CrPC

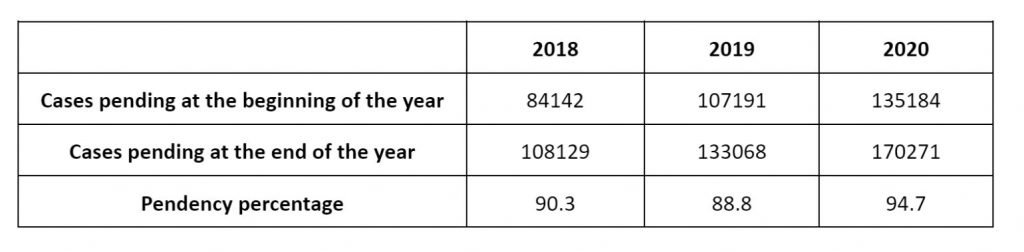

The purpose of providing a time bound trial in law is not only to ensure speedy justice but also to ensure that the child is not made to relive the abuse for a prolonged period of time. Despite this mandate and the provisioning of FTC schemes, disposal of cases under POCSO remains slow and pendency continues to mount. Statistics from NCRB reveal that the slowdown due to pandemic was not an exception, rather it merely aggravated the trend. Consider these numbers from NCRB statistics for the years 2018, 2019 and 2020:

Additionally, it was analysed that 69 per cent of cases disposed of by POCSO courts in 2019 took between 1 and 10 years, i.e. much beyond the mandated time period set in law.

It is evident that despite time-bound processes laid down in law since the enactment of POCSO in 2012, huge pendency continues to plague POCSO trials. Only a marginal reduction is seen after establishment of FTCs for POCSO trials in 2019 and even the nominal gains made in 2019 seem to have been undone in 2020 as pendency shot up due to the pandemic.

Fast Processes and Fast Acquittal in POCSO?

Along with high pendency, POCSO is also saddled with consistently low conviction rates. According to NCRB data, in 2018, the conviction rate stood at 34.2%, it was 34.9% in 2019, and improved marginally to stand at 39.6% in 2020. More cases resulting in acquittal is problematic because it either indicates that an innocent person had to go through the harsh rigours of the criminal justice system or that a guilty person was let free because of lapses in investigation or prosecution. There have also been few studies which have looked at the correlation between the time taken for completion of proceedings and the decisions of the Courts.

The Centre for Child and the Law at the National Law School of India University, Bangalore undertook an analysis of judgments of Special Courts under POCSO in five states (Delhi, Assam, Maharashtra, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh) and noted the following in its 2018 report:

- Reasons for delay in completion of trial, wherever recorded, were mostly due to time taken to complete investigation, obtain forensic reports, file charge-sheet leading to delays in recording of the evidence.

- The rate of victims turning hostile and rate of acquittal were the highest in cases in Maharashtra which were disposed within one year.

- But in Assam, the rate of victims turning hostile increased with an increasing gap between lodging of the FIR and recording of evidence.

- In Delhi, the conviction rate was low for cases disposed within a year and improved for cases disposed between one and two years.

In another study, Centre for Law and Policy Research analysed the working of Special FTCs for sexual assault and child sex abuse in Karnataka and found that the Special FTCs recorded a conviction rate of only 16.8% and Special Courts recorded a conviction rate of 7.8% for the analysed judgments delivered in 2013 & 2014. It also found that:

- The primary reason for the large number of acquittals was witnesses turning hostile, but the prosecution also did not make an effort to present other evidence and courts did not question the suspicious circumstances for witnesses turning hostile.

- Courts did not appreciate the evidence properly and the reliance on unconstitutional tests like the two-finger test and references to character or prior sexual history of the victim were rampant.

Enduring Questions

While sufficient research has not been done to study whether the mandate for quick disposal of cases leads to poor investigation or lapses in prosecution, and improper appreciation of evidence and thus low conviction, it is not beyond the realm of possibility. At the same time, delays and protracted proceedings can also vitiate the trial as it can be burdensome for the victim and her family to pursue the matter. Possibilities of the accused being released on bail and threatening or influencing the witnesses also increase with time. Delays can also be detrimental to the mental and psychological health of the victims.

It is imperative to understand that quick procedures, especially when the number of POCSO cases being reported is rising every year, may not yield justice in the absence of adequate facilities and human and financial resources to provide the same attention to every case. While the speed of the Rajasthan case – completion of investigation in 18 hours and completion of trial in 9 days – may provide the victim with ‘relief’, it may not necessarily ensure justice in a broken criminal justice system or adequately address the rights of the accused. More research is needed to understand the impact that time has on trials under POCSO and design procedures which are quick and child friendly but at the same time, practically feasible and oriented towards securing meaningful justice.